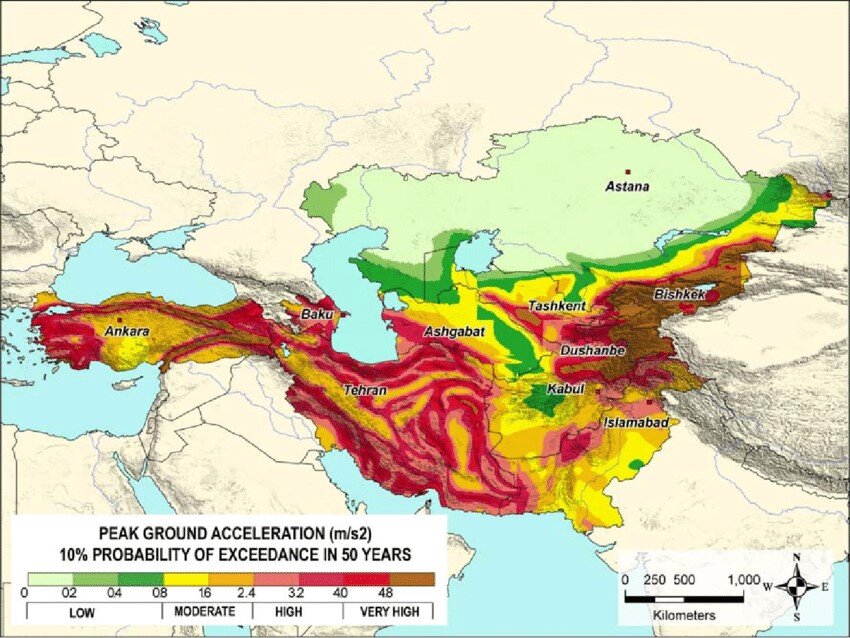

Tehran-Eurasian-Arabian tectonic plate collisions cause structural interactions with important seismic activity along fault systems in the Alborz Mountains and the Caspian Sea region.

The Alborz Mountain Belt is a major seismic zone with active faults such as the North Alborz and Mosha faults. These faults range from Jajam (east) to the Aras River (northwest) and affect cities such as Dongang, Semnan, Tehran (Ray), Kazbin and Aldabil.

On the coast of the southern Caspian Sea, high-risk areas such as Ramsar and Rasht are located near the Taresh Moogan fault. The Alborz-caspian boundary is prone to major earthquakes due to the compressive structure regime.

Major Historical Earthquakes

Damghan (856 AD) is the biggest historic event known as the most deadly earthquake (M-7.9), killing around 200,000 people. It devastated the Silk Road city of Kumis (near modern Donggan), highlighting the risk of earthquakes along ancient trade routes.

743 Caspian Gates Earthquake: Recorded in Byzantine sources, this event occurred near Darvent (Russia) or Talish (Iran). Its scale continues to be discussed, but the document highlights the long-standing seismic activity of Caspia Region 4.

Yorjan/Gonbad Kavas (958 A.D.): A destructive earthquake damaged the iconic Gombad Kavas Tower, highlighting long-term seismic activity in northeastern Iran.

Manjil (June 20, 1990): The M7.3 earthquake near Rasht and Rudbar killed about 16,000 people, disrupted infrastructure, highlighting the vulnerability of the Alborz-Caspian transition zone.

Ardabil (28 February 1997): M6.1 Quake near Meshkinshaal killed about 1,500 people in connection with the Sabara volcanic area and the Arbors-Azabaijan earthquake zone.

Talesh and Caspian Region: In 2012, the Ahar Fault was connected, recurring activity, including the M6.4 Varzeghan earthquake near the Azerbaijan-Iran border.

Ancient roads and earthquake zones

Corridors on the Silk Road through cities such as Dongang, Semnan, Lei (Tehran), and Kazbin were important seismic zones along active faults or aggressive faults.

The 856 Qmis (Damghan) earthquake exemplifies the earthquake threat to these routes. The Eastern Alborz went to the Caspian Sea region, where the historic earthquakes of Jajam and Gombad crossed a fault zone that reflected their seismic activity.

The seismic zone in the Ardabil area was recently represented by the Golestan Ardabil M6.1 earthquake on February 28, 1997.

Rapid urbanization of the Caspian coast from Astara to Rasht, Ramsar, Charus, Nuru and Behaaa has developed along the northern hilly areas of Albozbert, increasing seismic risk due to higher exposures associated with larger population accumulation. Inadequate construction practices exacerbate risk.

The Moha and North Alborz faults in the belt in southern Alborz are seismically active due to the structural regime of Alborz Caspians, and historical earthquakes affect ancient and modern settlements alike.

The ancient road (Silk Road) coincides with fault systems, exposing historic cities repeatedly to seismic events. Continuous monitoring and remodeling of infrastructure is essential to mitigate the risks of culturally and economically important zones.

The ancient trade network and the dangers of modern earthquakes highlight the interaction between natural forces and human settlements in the unstable northern regions of Iran.

The southern coast of the Caspian Sea is located within the Alborz seismic zone, where active faults such as Mazandaran, Alborz, Rahijan and Astara frequently generate earthquakes. These faults are part of a wider collision between the Eurasian and Arabian plates.

The area is prone to liquefaction, landslides and subsidence due to soft sedimentary soils and groundwater levels, exacerbating earthquake risk

The coastal plains of Caspia, especially areas such as Golestan and Mazandara regions, remain extremely vulnerable to earthquakes up to M5 due to their active and dense faults. Recent stochastic models integrate macrosemic data to assess hazard intensity.

These highlight the contradictions between historical records and current risk maps, and encourage better readiness for cities near active faults like Tehran.

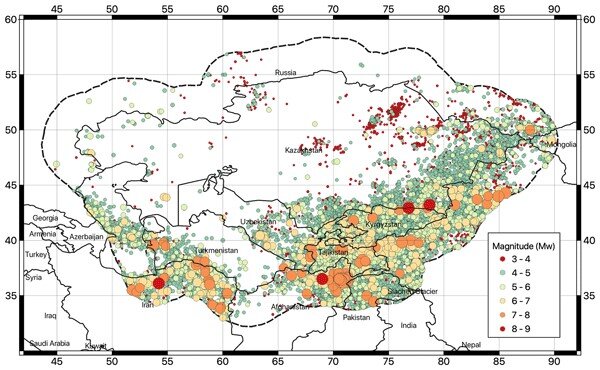

Seismic activity in Central Asia is being driven by the India-Iourasia collision, along with major fault systems in the Tien Shan, Pamir and Zongalian regions. The Dzhungarian fault in Kazakhstan shows evidence of prehistoric earthquakes up to MW 8.4.

The most important historical earthquakes known in the Central Asian region:

6th October 1948 Ashgabat earthquake (MW 7.3): The Soviet Union’s SSR destroyed the capital of Turkmenistan, killing about 110,000 people.

On July 10, 1949, the Kite earthquake (MW 7.5) in Garm Surveillance of the Soviet Union’s Tajik SSR caused about 7,200 casualties, causing a massive landslide in Tajikistan, filling the entire village.

Prehistoric giant events: paleoearthquake studies reveal large recurring earthquakes (e.g., MW 8.4 of the dzhungarian fault), highlighting the local capacity for catastrophic rupture.

Faults below cities such as Almaty (Kazakhstan) and Dushanbe (Tajikistan) pose a direct threat. The Zarisk Range Front Fault near Almaty has burst twice in the last 10,000 years.

Improving the resilience of these regions requires the integration of updated building codes, public education, and historical data into modern seismic models to address vulnerabilities.

Historical seismicity in the Ilancasian Sea and Central Asia highlights the persistent threat posed by active tectonics. Advances in hazard assessments improve risk insights, but sociopolitical and infrastructure challenges remain important barriers to disaster resilience.

Future efforts should prioritize interdisciplinary collaboration and community engagement to effectively mitigate these risks.