Israeli-German relations in the 1980s and 1990s were one of the most sensitive and dynamically evolving friendships in postwar international relations. Based on Holocaust trauma, relations between Germany and Israel have been transforming for many years from moral responsibility to practical cooperation, depending on internal political reasons, and in response to changes in the international situation.

The early 1980s were a time of high tension, especially since the election of Israeli Prime Minister Menachem began in 1977. He had a fierce debate with West German Prime Minister Helmut Schmidt, and announced in 1981 that relations reached Nadir and that Germany would sell tanks to Saudi Arabia, contrary to his wish to begin.

He publicly attacked at Schmidt, referring to his Welmahat past and accusing him of not “knowing” the suffering of Jews. The conflict uncovered the vulnerability of so-called “special relationships” and raised questions about whether Germany would remain on the fence between its historical guilt and the growth of geopolitical ambitions in the Arab world.

Venice Declaration and Europeanization of German Policy

The 1980 Venice Declaration was supported by West Germany and the European Economic Community (EEC), raising concerns in Israel. It approved the Palestinian self-determination and indirectly acknowledged the PLO, a change that Israel deemed betrayal. However, for Germany, this was the “Europeization” of Middle Eastern policies, an attempt to join forces with European partners, although it does not appear to be different from Israel alone. This move towards multilateralism will develop to become a signature of Germany’s foreign policy.

The Lebanon War of 1982

Another important intersection was the 1982 Lebanon War. When Israel besieged Beirut in refugee camps and slaughtered the Palestinians, it created moral discomfort in Germany. The West German government did not say anything publicly, but conversations within West Germany became negative.

There have been changes between generations. I want to not succumb to feelings of guilt about the Holocaust, but I want to see Israeli policies being questioned through the prism of human rights. Such internal debates have pushed the boundaries of German traditional solidarity with Israel and demonstrated a greater willingness to move more independently on issues of Middle Eastern politics.

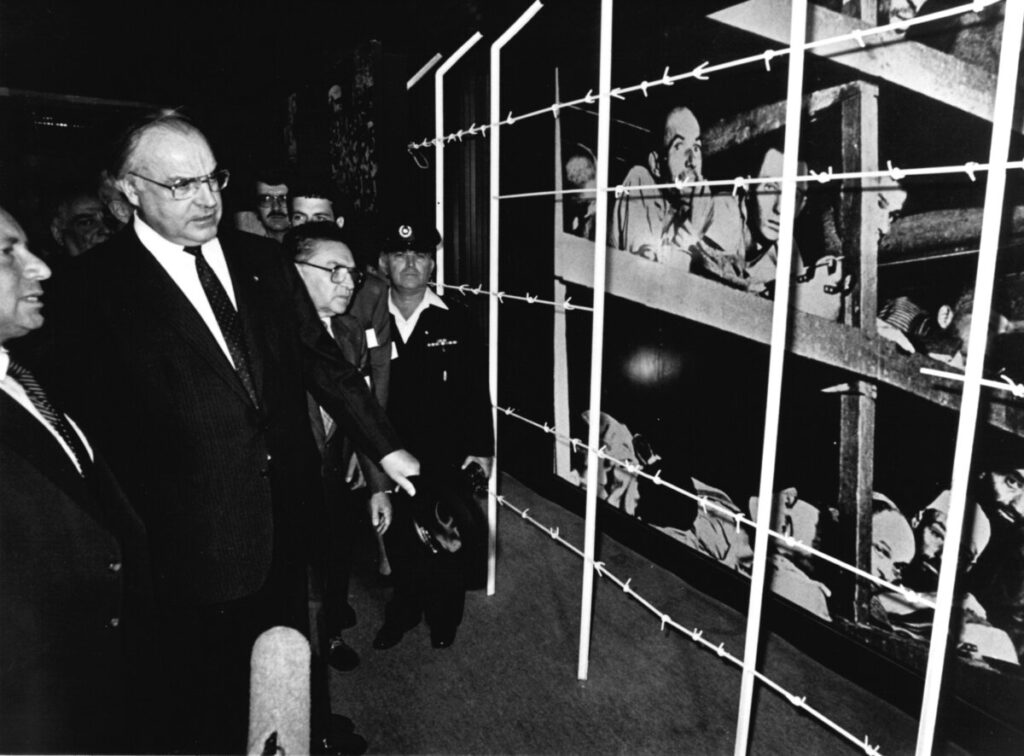

Call Era: Pragmatism and Reconciliation

In 1982, the Prime Minister of Helmutcole saw a breakthrough. Cole wanted to make German mainstreamism mainstream while ensuring close ties with Israel. In his 1984 speech to Knessett, entitled “Post-Birth Mercy,” he sparked rage when he suggested that post-war Germans must feel utter Nazi guilt.

Despite verbal vias, Cole’s administration actually did a lot to strengthen relations between Germany and Israel. Germany quickly emerged as one of Israel’s closest European allies as the two countries expanded cooperation in trade, technology and defense.

But the relationship has changed. Once defined by guilt and moral responsibility, by the decade of the 1990s it was more animated by interest and practical considerations. However, both sides show that they understand that their relationship needs to be readjusted in light of changes in German policy as Germany sought a new role and new weight in global issues and Israel sought to compete with the new structure of the region.

In summary, the 1980s and 1990s can be seen as time frames for changes in relations between Germany and Israel. What began as judged, frequently precarious events almost always, if not always, ended up measuring collaboration. This transformation was not only a historical calculation, but also a product of diplomatic necessities in a fluid world.

1990s: Unification, crisis, strategic partnership

The 1990s were an important decade in the development of German-Israel relations, from a burdensome past to practical, multidimensional partnerships. It was characterized by a crisis that strained trust and close cooperation based on German reunification, regional change, and a joint commitment to memory and security.

Germany’s unification in 1990 caused great uncertainty in the Israeli and Jewish diaspora communities. For many, the division of East and West Germany after World War II represented the consequences of Nazi atrocities, and unity raised concerns about a revival of German nationalism. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir has publicly said he is worried that Unified Germany will rekindle dangerous ideology.

However, the symbolic, deeply reconciliatory gesture came in April 1990 when East Germany’s new parliament officially assumed responsibility for Nazi crimes and apologised for previous anti-Israel policies. Visits by both German parliament representatives to Israel conveyed new preparations to consider history and restore confidence.

Unity has renewed its obligation to support its moral and political commitment to Israel for Germany. For Israel, it was a test of Germany’s democratic maturity and confidence in its ability to agree with the past and look to the future.

Doctrine of the Persian Gulf War and “historical responsibility”

Tensions erupted once it was revealed that some German companies had supplied Iraq with chemicals and electronics that could be used in the war.

This has issued an alarm in Israel about possible chemical attacks, especially given the painful memories of the Holocaust for survivors. To cope with the growing fear, German Hans Dietrich Genscher visited Jerusalem, and Germany later sent two submarines to Israel.

This situation reinforced Germany’s view of responsibility for history Verantwaltun, or Israel, and became an important part of its foreign policy. Business interests also pointed to the limits of its commitment, as it means that sensitive technology could fall into the hands of Israeli enemies.

In the 1990s, Germany worked to strengthen relations in the Middle East, often intervening as a mediator between Israel and its neighbors. These efforts had set Germany’s goal of being the bridge builders in the region, but they raised some concerns about their willingness to interact with hostile countries in Israel.

Essen Declaration and Israel’s “special status” in Europe

A significant moment came in December 1994 with the Essen Declaration, in which Prime Minister Helmutkohl secured Israel’s special status within the European Union. This has allowed Israel to have better access and political opportunities to the European market. For Germany, it was a sign of Israel’s continued commitment to its role in Europe and its role.

Generational change and civic society

Despite all the changes, there was still some tension. The Holocaust is an important part of Germany-Israel relations, and German leaders often said that Israel’s security is important to Germany. Still, this support wasn’t necessarily strong. Germany began to more openly criticize Israel’s policy of reconciliation, with the shift to international law and human rights showing a shift in foreign trade.

The younger generation also changed how these two countries interacted. When memories of the Holocaust faded, many young Germans and Israelis looked for new ways to connect. Programs focused on cultural, education and community work have begun to flourish. However, this change sparked some disagreements as people began to openly debate about memory, identity, and how far criticism should go.

“Europeanization” of German policy

Another change in relations between Germany and Israel came from Germany becoming more involved in the EU. Because of their close cooperation with the European Union, Germany often framed Middle Eastern views as part of a broader European approach. This gave Germany a diplomatic advantage, but somewhat lessened how unique its relations with Israel became.

By the late 90s, the ties between Germany and Israel had changed dramatically. What began as a relationship filled with guilt and pain has turned into an actual partnership. Germany has become a key player in Israel’s most powerful ally in Europe, the EU, and has become a partner in both crisis and peace initiatives. Relationships are still evolving, influenced by history, changing identity and changing world landscapes that balance memory with real-world politics.